Gone Fishin': Justin.Tv's Live Video Broadcasting Architecture

Thursday, November 15, 2012 at 9:15AM

Thursday, November 15, 2012 at 9:15AM This is one of my favorite posts for a couple of reasons. I think it gives a lot of useful information in an interesting space. And Kyle Vogt was just a real pleasure to talk to. He was very helpful and forthcoming, which makes the whole experience better for everyone.

The future is live. The future is real-time. The future is now. That's the hype anyway. And as it has a habit of doing, the hype is slowly becoming reality. We are seeing live searches, live tweets, live location, live reality augmentation, live crab (fresh and local), and live event publishing. One of the most challenging of all live technologies is that of live video broadcasting. Imagine a world in which everyone becomes a broadcaster and a consumer of video streams, all in real-time (< 250 msec latency), all so you can talk and interact directly without feeling like you are in the middle of a time shift war. The resources and the engineering needed to make this happened must be substantial. How do you do that?

To find out I talked to Kyle Vogt, Justin.tv Founder and VP of Engineering. Justin.tv certainly has the numbers. Their 30 million unique monthly visitors even outshine YouTube in the video upload game, reportedly uploading nearly 30 hours per minute of video compared to YouTube's 23. I asked for an interview after listening to an interview with Justin Kan, another Founder of the eponymously named Justin.tv. Justin talked about how live video was fundamentally different than YouTube's batch video approach, where all the video is stored on disk and replayed later on demand. Live video can't be made by pushing video faster, it takes a completely differently architecture. Since the YouTube Architecture article is the most popular article ever on this site, I thought people might also enjoy learning about live side of the video world. Kyle was unbelievably generous with his time and insight into how Justin.tv makes all this live video magic happen, going way beyond the call, providing a tremendous number of juicy details. Anyone building a system can learn something from how they run their business. I can't thank Kyle enough for putting up with my never ending prodding.

As the emphasis shifts from batch to real-time, the steps Justin.tv are taking is also happening across the industry. We've mostly learned how to create scalable batch systems. Real-time requires a different architecture. LinkedIn, for example, has spent a lot of energy on building a real-time search that is updated nearly instantaneously, even for complex queries. They accomplish this by partitioning data in memory and writing their own highly specialized systems to make it work.

Google is perhaps the perfect example of the change to real-time. When Google was just a little bitty oogle, they lazily updated their search indexes every month. This is a batch model, which meant designing an infrastructure for storing lots of data, which required high throughput, not low latency. Times have changed. Now Google is hyped up on Caffeine and updates continuously. They've had to make many architectural changes and completely overhaul their stack to support customer facing applications, like Gmail, where latency matters. And Google won't be the only ones that have to learn how to deal with the new real-time.

Information Sources

- Interview with Kyle Vogt, Justin.tv Founder and VP of Engineering.

- Justin Kan on Getting Traction by Gabriel Weinberg.

- AWS the Startup Project by Kyle Vogt. This is Justin.tv's architecture as of over 3 years ago.

- Inside live video service Justin.tv. Robert Scoble's interview with Evan Solomon, Justin.tv's VP of Marketing.

Platform

- Twice - custom web caching system. (http://code.google.com/p/twicecache/)

- XFS - file system.

- HAProxy - software load balancing.

- The LVS stack and ldirectord - high availability.

- Ruby on Rails - application server

- Nginx - web server.

- PostgreSQL - database used for user and other meta data.

- MongoDB - used for their internal analytics tools.

- MemcachedDB - used for handling high write data like view counters.

- Syslog-ng - logging service.

- RabitMQ - used for job system.

- Puppet - used to build servers.

- Git - used for source code control.

- Wowza - Flash/H.264 video server, plus lots of custome modules written in Java.

- Usher - custom business logic server for playing video streams.

- S3 - small image storage.

The Stats

- 4 datacenters spread through out the country.

- At any given time there's close to 2,000 incoming streams.

- 30 hours per minute of video is added each day.

- 30 million unique visitors a month.

- Average live bandwidth is about 45 gigabits per second. Daily peak bandwidth at about 110 Gbps. Largest spike has been 500 Gbps.

- Approximately 200 video servers, based on commodity hardware, each capable of sending 1Gbps of video. Smaller than most CDNs yet larger than most video websites.

- About 100TB of archival storage is saved per week.

- The complete video path can't have more than 250 msecs of latency before viewers start losing the ability to converse and interact in real-time.

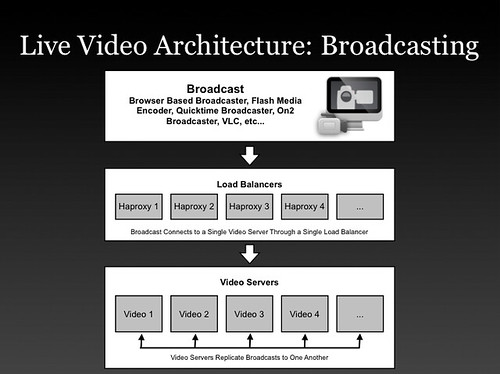

The Live Video Architecture

- Why is live video difficult? It seems like you just need a lot of bandwidth, keep it all in memory, shuffle the streams around, and you are done. Simple. Not that simple. If you can't just do YouTube faster for live video, what makes live video such a challenge?

- Live video can't hiccup, which means you can't oversubscribe bandwidth. YouTube when they started over subscribed bandwidth. They had like 10 gigs of traffic out a 8 gig pipe. That works because the player just has to buffer. With live video if you exceed your network capacity even for a fraction of a second every single viewer will see buffering all at the same moment. If you have more demand than capacity it just won't work, everyone will constantly see buffering. Having network capacity was very important and something they had to do right. So they came up with their peering architecture . They also have way more capacity than they need available if they should require it.

- Graceful overflow to a CDN when they do overflow. Sometimes they do run out of capacity and they worked hard on gracefully being able to overflow to a CDN. Usher handles this logic. Once out of capacity new viewers are sent to a CDN.

- Building systems that appear to have 100% up time yet have the ability to take machines out of production slowly and gradually for maintenance. This is very difficult when viewers can quickly notice any problems and immediately talk to each about it over chat. With the chat feature there's no hiding problems. Users have very high service expectations so problems must be dealt with gracefully. They have to wait until everyone is done using a server before it can enter maintenance mode. It's a very slow rotation. Sessions are never interrupted. Your usual website can have a number errors that few people will notice.

- The biggest problem they have is controlling flash crowds, when a lot of people want to watch the same thing at the same time. It's a huge amount of incoming traffic. So they needed to create a way to adapt load in real-time across all their video servers and datacenters. That mechanism is Usher.

- Usher is custom software they created to manage load balancing, authentication, and other business logic for playing streams. Usher calculates how many servers to send each stream in order to ensure there's always optimal load. This is their special sauce and is what sets their system apart. It decides in real-time how to replicate streams to servers based on:

- How much load a particular datacenter has.

- Individual load of all the servers.

- Latency optimization.

- The list of servers where a stream is available.

- Your IP address to figure out what country you are from.

- Your IP address in their route database to see if they peer with your ISP.

- Which datacenter where the request came in and they try to send you to a video server in the same datacenter.

- Using these metrics Usher can optimize on pure cost to send you to a server where it's going to be free or they can send you to a server that's closest to where you are to optimize for better latency and performance. They have a lot of dials to turn and have very fine grained control.

- Every server can act as an edge server (where the video is streaming out of to a viewer) and an origin server (where the video is streaming into from a broadcaster). Based on load a stream may be available on one server or every server in the network. It's a dynamic and constantly changing process.

- The connections of how streams are replicated between servers looks like a weighted tree. The number of streams is sampled constantly. If a certain stream has a high velocity of new incoming viewers then that stream is replicated to a few other servers. And the process repeats, building up a tree shape, potentially including all the servers in the network. This process can execute in as little as three seconds.

- The entire video stream stays in memory from the time it hits the origin server to when it's copied to other servers and when it's copied to viewers. There's no disk path involved.

- Flash is used to be as accessible as possible, which uses the RTMP protocol. There's an independent session for every stream. It's fairly expensive because of the protocol. Multicasting or P2P techniques are not used. Downstream ISPs don't support multicast. They did consider using multicast internally to copy streams between servers, but since they have control over their network and have plenty of cheap bandwidth internally, there's not as much of a benefit. It's also difficult to do at a fine grain level since their algorithms are optimized to put the minimum number of streams on each server. It would be more complicated than the gain they would get.

- Usher is used, via an HTTP request, to decide which video server to use to handle a stream. The video servers are fairly dumb, the overlay logic controlling the serving topology is managed by Usher.

- Originally started in AWS, then moved to Akamai, and then moved into their own datacenters.

- Moved out of AWS because: 1) the cost, 2) the network was too slow for their needs. Live video is bandwidth intensive so having a fast, reliable, consistent, low latency network is key. With AWS you have no control over these factors. Your are running on a shared network that is vastly over subscribed, they couldn't do more than 300 Mbps. They really like the ability to dynamically scale and the cloud API, but couldn't get over the performance and cost issues.

- Three years ago they calculated their cost per customer with the various solutions as: CDN $.135, AWS $.0074 Datacenter $.0017. The CDN cost has gone down, but their datacenter cost is roughly the same.

- The point of having multiple datacenters is not for redundancy, it's to be as close as possible to all the major peering exchanges ("voluntary interconnection of administratively separate Internet networks for the purpose of exchanging traffic between the customers of each network"). They picked the best locations in the country so they would have access to the largest number of peers.

- Cost savings. This means a large percentage of their traffic doesn't cost them any money because they are connected directly to these other networks.

- Performance gain. They are directly connected to what they call "eyeball" networks. An eyeball network is one that has a lot of cable/DSL subscribers in their network. Peering with eyeball networks makes more sense than peering with "content" networks (like CDN's, other websites, etc), since Justin.tv serves traffic primarily to end users. They are one network hop away which is great for performance. in most of the cases these arrangements are settlement free, no one pays any money, you just hook up.

- They have a backbone network to get the video streams between datacenters.

- The selection process for a finding a peer is to select whomever is willing to peer will them. It's hard to find partners.

- Bandwidth billing is complicated and non-standard when you buy in bulk. They bill at 90th and 95th percentile rather than actual usage.

- While video streams are not streamed from disk, video is archived to disk. The origin server, the server picked to handle an incoming stream, records a stream on local disk, that recording is then uploaded to long term storage.

- Every second of video is recorded and archived.

- The archive storage looks like YouTube, just a bunch of disks. XFS is used as the file system.

- This architecture spreads the writes of broadcasts throughout the servers. It's a lot of work to write thousands of streams simultaneously.

- By default streams are kept for 7 days. A user can manually specify clips which can be stored forever.

- Video files are easily partitioned across disks.

- Their operating system is tuned to handle flash crowds as flash crowds put a lot stress on their systems. The network stack is tuned to handle a large number of incoming connections a second. Since they don't have a lot of disk activity going on they don't need to tune much else.

- The client participates in the load balancing logic, which is one of the reasons they require the use of their own player. TCP is fairly good at handling their typical data rate of a few hundred kbps, so no special manipulation of the TCP settings are necessary.

- The number of video servers may seem a little low for their traffic because with Usher they can run each video server to full capacity. Load balancing makes sure they are never over their limit. The load is mostly in-memory so they can drive the network at full capacity.

- Servers are bought from Rackable a whole rack at a time. They just roll 'em in all prewired.

- Added real-time transcoding which can take in any format of stream, change both the transport layer and the codec, and stream it out in the new format. There's a transcoding cluster that handles the transcoding. Transcoding sessions are scheduled through a job system that spins off transcoding sessions within the cluster. All their servers can be transcoding servers if the demand outstrips their transcoding farm.

- Happy with the trend of moving away from heavy protocols and towards using HTTP Streaming, which scales very well with existing technologies. The one problem is there isn't an emphasis on latency and real-time. People fudge and say it's real-time if it's between 5 and 30 seconds behind, but that doesn't work for live broadcast to thousands of people that are trying to converse and interact in real-time. There can't be more than 1/4 second of latency.

The Web Architecture

- Peak request volume is 10 times higher than their steady state traffic. They must be able to handle big events.

- Ruby on Rails is used as the front-end.

- Every page in the system is cached using their custom built caching system called Twice. Twice acts as a combination light weight reverse proxy and templating system. The idea is to cache every page and then make it easy to merge in what is different for each user.

- Using Twice each process can handle 150 requests per second as apposed to the backend which can process 10-20 requests per second, a 7x-10x gain in the number of web pages they can serve. Over 95% of pages are served out of cache.

- Most of dynamic pageviews are rendered in under 5ms since the processing required is minimal.

- Twice has a plugin architecture so it can support application specific features like:

- Add geographical information.

- Lookup a Twice cache key or a MemcacheDB key.

- Automatically cache data like the user name without having to touching the application server.

- Twice is custom made to fit their needs and environment. If starting a new Rails app one engineer thought using Varnish might be a better idea.

- Web traffic is served out of one datacenter. The other datacenters are there to serve video.

- They have added monitoring to everything. Every click, page view, and action is measured to help improve service. Log messages from the front-end, web call, or from an application server are converted to syslog messages and forwarded through syslog-ngto a single log host. They scan through the data, load it into MongoDB, and run queries on MongoDB.

- Their API is served from the same application servers as the website. It uses the same caching engine so scaling the API is accomplished by scaling the website.

- PostegreSQL is their primary database. The structure is straightforward with a master and a set of read slaves.

- With their type of site they don't have a lot of writes. The caching system handles the reads.

- They found that PostgreSQL doesn't handle a large number small number of writes very well, that really bogs it down. So MemcachedDB is used for handling high write data like view counters.

- They have a chat cluster to handle their chat functionality. If you go to a channel you'll get sent to one five different chat servers. Scaling chat is a easier than scaling vide because it's text and it partitions well. People can be split up into different rooms which can be served on different servers. They also don't have chats with the 100,000 people watching a channel. What they do is assign people into rooms of 200 people each so you can have a meaningful interaction in a smaller group. This also helps with scaling. I thought this was a pretty clever strategy.

- AWS is used to store profile images. They haven't built out anything that can store lots of small images so it's easier to use S3. It's very convenient and doesn't cost very much so there's no reason to spend time on it. If it does become a problem they deal with it then. Their images are frequently used so they are very cacheable, there's no long tail problem to deal with.

Network Topology and Design

- The network topology is pretty simple and flat. Each server has dual 1 gig cards to the top of the rack. Each rack has multiple 10 gig interfaces out to the core routers. For switches they found Dell Power Edge switch, which aren't all that good for L3 (TCP/IP), but works great for L2 (ethernet). It will push 20 gigs per switch all day long and is very inexpensive. The core routers are Cisco 6500 series. Keep it simple. They want to minimize the number hops to minimize the latency and also to minimize the amount of processing per packet. Usher handles all the access control and other logic rather than networking hardware.

- Use multiple datacenters to take advantage of peering relationships and be able to move traffic as close as possible to the user.

- Heavy peering and interconnection with other networks. Multiple providers with transit so they can pick the best path. If they notice congestion to a certain network they can pick a different route. They can look at the IP address, look at the time, and figure out the ISP.

Development and Deployment

- Puppet is used to build servers from bare metal. They have about 20 different types of servers. Anything from a database slave to a memcache box. With Puppet they can turn a box it into whatever they want.

- They have two software teams. One is the product team and the other is the infrastructure team. The teams are pretty flat, about seven or eight people in each team. There's a product manager for each team.

- They typically hire generalists, but do have network architecture and database specialists.

- Any branch can be pushed to a staging or production within minutes using a web based deployment system.

- QA has to sign off before is going into production. Usually takes 5 to 10 minutes.

- Git is used for source code control. They like that you can write a branch, a 20 or 30 line feature, and it's merged in with everyone elses branches that are currently on production. Things are very separate and modular. You can easily pull back certain features as apposed to Subversion where you have to pull back entire commits and anyone who committed some non offending code is out of luck.

- Every few days everyone tries to merge into the master branch in order to eliminate conflicts.

- They release many small features: between 5 and 15 deployments a day to production! Range form 1 line bug fixes to a larger experiment.

- Database schema upgrades are done by hand. A well-hacked version of ActiveRecord migrations works across their replicated databases. There are a number of different staging environments in which tests are conducted before deploying changes to production.

- Configuration file changes are handled by Puppet.

- Every feature is basically an experiment. They are tracking virality and retention on every major change they make. It's an experiment because they are trying to figure out which changes actually improve the metrics they care about.

The Future

Their goal is grow by an order of magnitude. To accomplish this they plan on making the following changes:

- Shard their video metadata system. Metadata load grows exponentially with the number of streams and number of servers so as they grow sharding is needed to scale. Cassandra is being considered.

- Shard their web database.

- Build a copy of their primary datacenter for disaster recovery purposes.

Lessons Learned

- Build vs Buy . They've made the wrong decisions many times in the past on building their own or buying something off the shelf. For example, they built a video server at first when they really should have bought. Software engineers like to build custom, but there are many benefits to using software maintained by an open source community. So they've come up with a better process for making those kind of decsions:

- Is this project active? Maintained? Patched?

- Are other people using it? Can you ask someone else how to modify it?

- Extensibility matters. They usually need to make changes.

- Can we build it faster, get better performance, or get some feature we need if buld it ourselves? This is a slippery slope because the feature argument can always be used to build it yourself. Now, like with Usher, they consider if they can build a feature outside and ontop of another system. Building Usher as the core backbone of their video scalability on top of relatively dumb video servers is an excellent example of this strategy.

- Worry about you do, not what others do . Their goal is to have the best system, the most up time, and perfected scalability. It took 3 years to develop the tech to to handle millions of simultaneous broadcasting.

- Don't outsource. The value of what you learn is in experience. Not in code or hardware.

- Consider everything an experiment. Measure everything. Split test. Track. Measure. It's worth it. Do it from beginning. Have good instrumentation. For example, they append a hashtag to a copied URL so they can tell if you share a link. They went from a period of no measurement to hyper measurement. By rewritting the broadcast process they increased the conversion by 700 percent. They want the site to be fast, responsive, for pages to load faster, to serve video better. Every millisecond of delay squeezed out of the system brings in more broadcasters. They have 40 experiments they would like to run on the flow of getting a user to become a broadcaster. For each experiment they want to look at the retention rates of the broadcaster afterwards, the virality of the broadcaster, conversion rates, then make an intelligent decision on which changes to make.

- Most important thing is to have an understanding of how your site is shared and optimize it . They were able to increase shares by 500 percent by decreasing the menu depth it took to share a link.

- Peaks don't grow as quickly as everything else . Serving 10x as many total video views would only require scaling the system by 3x-4x.

- Use homegenous interchangable parts. Using common building blocks and infrastructure means that systems can be immediately repurposed in response to dynamic load.

- Identify what is important and execute . Having network capacity was very important and something they had to do right from the very beginning.

- Run systems hot. Utilize the full capacity of your systems. Why leave money on the table? Build systems that can respond to load by properly distributing it.

- Dont spend time on what is unimportant. If it's very convenient and doesn't cost very much, there's no reason to spend time on it. Using S3 for profile images is an example of this strategy.

- Support users in what they want to do, not what you think they should do. Justin.tv's end goal seems to be to turn everyone into a broadcaster. They are trying to make that process as easy as possible by getting out of the user's way as much as possible while the user's experiment. In the process they've found gaming is a huge use case. User's like to capture Xbox output and broadcast live and talk about it. Probably not something you would have thought to put in the business plan.

- Design for peak load. If you just design for steady state then your site will be crushed when a peak load occurs. In live video this is often a big event and if you mess up a lot of people will spread the bad word about you. Designing for peak load takes a whole other level of technology and the will to do the right thing architecturally. Engineering matters.

- Keep the network architecture simple. Use multiple datacenters. Use heavy peering and network interconnections.

- Don't be afraid to divide things up into more scalable chunks. For example, rather than have 100,000 people on a chat channel, split them up into more social and scalable groups.

- Real-time systems can't hide anything from users, this can make it difficult to convince users that your site is reliable. Users, because they are in a constant interaction with a real-time system will notice every problem and every glitch. You can't hide. Everyone notices. And everyone can communicate with each other about what is happening, in real-time. Very quickly users can develop the perception that your site is having problems when it's often a problem on the user's side. It can be difficult to convince people that your site is reliable. Under these circumstances it becomes even more important to communicate with your users; build in reliability, quality, scalability, and performance from the ground up; and design a user experience as simple and pain free as possible.

Related Articles

- YouTube Architecture.

- Hot New Trend: Linking Clouds Through Cheap IP VPNs Instead of Private Lines

- Peering at Data Center Knowledge

- Internet Peering Knowledge Center - Really cool diagrams and papers on peering.

- Life at a Startup by Bill Moorier.

Reader Comments (2)

As a mostly non-techie user of Justin.tv, I found this article very interesting. I also noticed a couple of things that don't seem quite right.

First, routine retention of past video streams WAS 7 days about a year ago. Then they moved it to 4 days, and then to 48 hours, which is the current policy. It was stated that this move was to reduce storage costs.

Second, justin.tv developers made a very big deal about moving off Rails and onto Django earlier this year. Apparently twitch.tv, the spin-off gaming site operated by justin.tv, still uses Rails.

One question: When Kyle mentioned costs per customer, it isn't clear what units are being described. Are those costs per viewer or per caster, or maybe it doesn't matter? Also, are those costs per hour, per minute, per day, or what? I was just curious about that.

Hey Gil,

The Gone Fishin' posts are older posts that I reposted while on vacation. So it's quite likely things have changed since it was originally posted. Sorry for the confusion.