The Performance of Distributed Data-Structures Running on a "Cache-Coherent" In-Memory Data Grid

Monday, August 20, 2012 at 9:15AM

Monday, August 20, 2012 at 9:15AM

This is a guest post by Ron Pressler, the founder and CEO of Parallel Universe, a Y Combinator company building advanced middleware for real-time applications.

A little over a month ago, we open-sourced a new in-memory data grid called Galaxy. An in-memory data grid, or IMDG, is a clustered data storage and processing middleware that uses RAM as the authoritative and primary storage, and distributes data over a cluster for purposes of data and processing scalability and high-availability. A common feature of IMDGs is co-location of code and data, meaning that application code runs on all cluster nodes, each instance processing those data items residing in the local node's RAM.

While quite a few commercial and open-source IMDGs are available (like Terracotta, Gigaspaces, Oracle Coherence, GemFire, Websphere eXtreme Scale, Infinispan and Hazelcast), Galaxy has adopted a completely different architecture from all other IMDGs, to service some usage scenarios ill-fitted to the other solutions.

All other IMDGs, as well as most distributed NoSQL databases (like Riak and Cassandra) employ what is known as distributed hash-tables (DHTs) to partition and locate data items in the cluster. DHTs assign a data item to one or more cluster nodes based on a static hash value computed for each item's key (those systems provide access to items by keys). This means that an item's owning cluster-node(s) can be easily located, and require just one network roundtrip per access in the worst case (for a read or a write). However, that one network roundtrip is also required in the common case.

Galaxy, on the other hand, dynamically migrates items among cluster nodes making a different tradeoff: accessing an item might take more than one network roundtrip in the worst-case scenario, but the common case requires no hops at all (note that this is not the same as write-through caches).

This tradeoff is suitable when the data and its access patterns induce a metric over the data-space, where nearby data-points are more likely to be accessed together (in the same query/transaction) than faraway points, and data items dynamically move in that metric space. Two examples are spatial data (the original motivation for Galaxy) and graphs. When an application accesses one graph-node, it is likely to access its neighbors in the same query, and unlikely to access distant nodes.

Galaxy borrows its design from that of CPU L1 cores, and this blog post explains the rational behind the design, so I won't expand further on this subject here.

Galaxy is meant to serve as a foundation for building distributed data-structures, and an analysis of one such structure is the main topic of this post.

Shared-state vs. Message passing

One issue that often comes up when discussing distributed systems is the question of message-passing architecture versus shared-state.

It is important to realize that all shared-state systems (even the shared RAM on your computer) are an abstraction implemented under the hood with message-passing. It is an abstraction that gives developers a very useful illusion.

When the shared state abstraction is used, performance issues normally arise only in the presence of write contention — when two independent processes attempt to write the same address/item concurrently. It is contention that requires the underlying implementation to pass messages, and it is this communication that derails performance, because it is usually done over a relatively slow channel.

So it is not shared state that performs slower than message-passing. It is contention that causes communication — which is slow. It can be claimed, though, that a message-passing architecture makes communication explicit and thus calls attention to it, while shared-state hides it behind an abstraction, making developers less aware of pitfalls. Nevertheless, for many applications (or software components) shared state is a natural and very convenient model — particularly for data stores.

A short overview of Galaxy's implementation and its implications

As the data-structure we're about to discuss is the B+-tree, in order to avoid confusion, we shall henceforth call the Galaxy cluster nodes machines, while the tree nodes will be called, simply, nodes.

But before beginning our analysis we need to describe, very concisely, how Galaxy is implemented; i.e. how Galaxy uses a message-passing foundation — a computer network — to provide the illusion of one large, shared memory space.

A full and detailed description is given in this blog post series, but here I'll provide a very short summary.

Every data-item in Galaxy (accessed not through a key, but using an ID assigned by the framework) is owned by exactly one machine at any given time, and may be shared by many. The item resides in the local RAM of both owner and sharers in an object called a cache-line (the name has been adopted from that used by L1 caches, the inspiration Galaxy's architecture). Item reads, therefore — both by the owner and the sharers — are serviced by RAM and require no network hops.

If a machine wishes to write an item, it must first request ownership over the item — if it not already the owner (requiring 1 network roundtrip) — and then invalidate the item's cache-line in all of its sharers (1 roundtrip * #sharers) to become an exclusive owner, and then the write can proceed in RAM. Quite often, the former sharers will again request to share the item for future reads, requiring another roundtrip per sharer. In total, the worst-case update of an item may require 1 + 2 * #sharers per update (Galaxy employs some heuristics to reduce write latency — fully discussed in the linked post series — but they are not relevant to our current discussion).

This may sound bad, but bear in mind that in most well-implemented distributed data structures, most items are not shared at all — as we shall see soon — and in the common case an update requires 0 network hops.

We will now analyze the performance of such a data-structure.

Amortized analysis of inserts to a distributed B+-tree

The data structure I have chosen for this discussion is the ubiquitous B+-tree. The B+ tree performs all search, insert and delete operations in logarithmic time, and has the following very desired property for our purposes: modifications (i.e. inserts and deletes) are normally done solely at the leaves, and only occasionally require modifications to inner nodes, with modifications being rarer the higher the node is in the tree. We will analyze amortized cost (the worst-case cost of a sequence of operations, each having a different individual cost) of the insert operation. But unlike traditional algorithm analysis, we will not count computer instructions required, but rather the number of network roundtrips, as those are the weakest link in the performance of any distributed system.

We will assume that the tree is implemented using Galaxy such that each node is one Galaxy data-item, and that each node has a capacity of b>2 children (b is the tree's fanout). We will denote the number of machines in the cluster as M, and the number of elements stored in the tree (the size of the data set) as n.

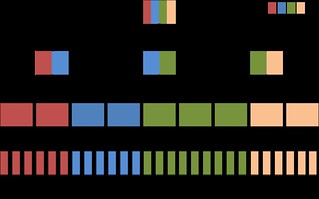

Let us also assume that some algorithm has distributed the nodes among machines such that below a certain level L of the tree, all nodes are exclusively owned by one machine — i.e. they have no sharers — and that the algorithm directs any operation to the machine best suited to execute it. ![]() so the vast majority of nodes are below level L.

so the vast majority of nodes are below level L.

The drawing shows how the nodes are distributed: each color represents a machine, and the nodes' colors denote which machines share the node. If a node has only one color, it is exclusively owned by one machine, and updating it entails no network roundtrips.

In addition to all the nodes below level L, each machines shares all of its owned nodes' parents, all the way to the root. This means that the tree's root node is shared by all M machines, the nodes at level 2 are each shared by ![]() machines, at the level below that by

machines, at the level below that by ![]() , and so on. Because of this, updating the root requires M network roundtrips, updating a node at the level below the root requires

, and so on. Because of this, updating the root requires M network roundtrips, updating a node at the level below the root requires ![]() roundtrips etc.

roundtrips etc.

Now, remember that the B+-tree insert operation first inserts the element into one of the leaves. If it overflows, the leaf splits into two — each new leaf containing half of the old leaf's element, and then inserts the new leaf as a child into the parent node. When the parent node overflows, it, too, splits, and the new node is inserted into its parent and so on.

We will begin the analysis when all nodes — leaves and inner nodes — contain ![]() children each (for simplicity's sake we assume b is even) — the minimum allowed by the B+-tree — and the tree is of height h (so the data-structure contains exactly

children each (for simplicity's sake we assume b is even) — the minimum allowed by the B+-tree — and the tree is of height h (so the data-structure contains exactly ![]() elements, because the B+-tree stores all data elements in the leaves).

elements, because the B+-tree stores all data elements in the leaves).

Let's now count the number of network roundtrips required, in the worst-case, by a sequence of ![]() consecutive insert operations, with

consecutive insert operations, with ![]() .

.

In the worst case, all inserts will hit the same leaf over and over. After the first ![]() inserts, the leaf will split. After

inserts, the leaf will split. After ![]() inserts, its parent node will split as well, and after

inserts, its parent node will split as well, and after ![]() . Eventually nodes at level L and above will split, and that will entail roundtrips. Occasionally, an insert will trigger a cascade of updates going all the way to the root, requiring all necessary roundtrips at all levels above L. So the total number of roundtrips for

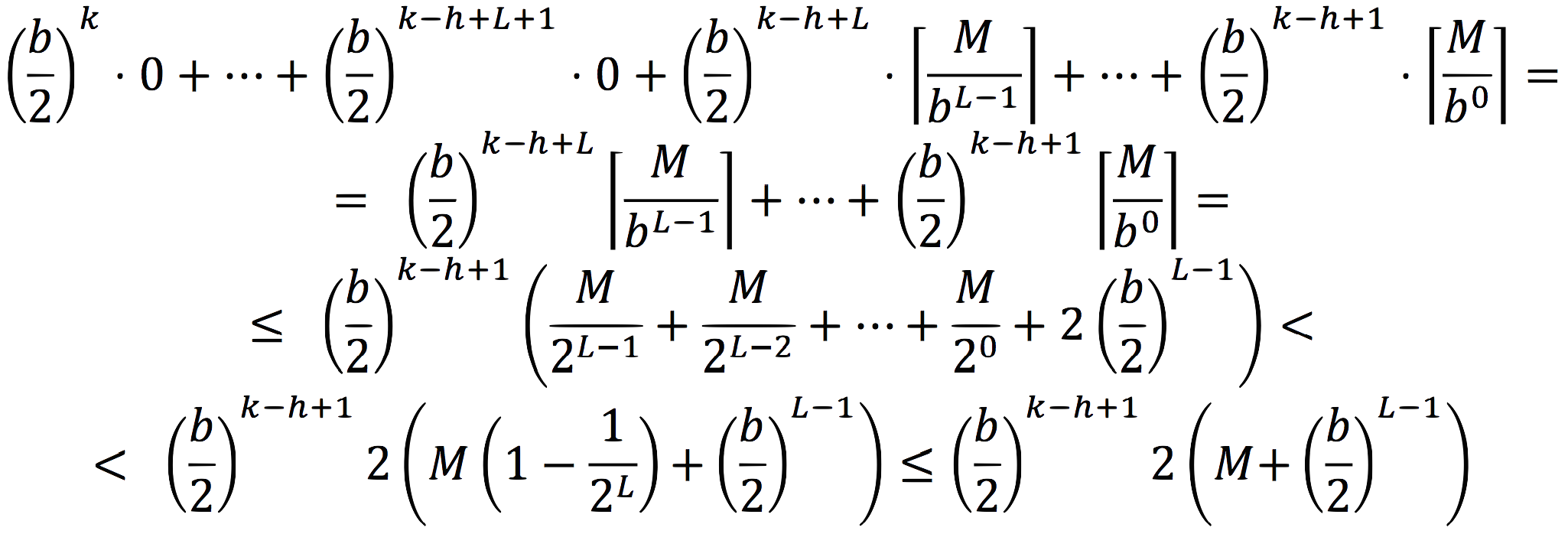

. Eventually nodes at level L and above will split, and that will entail roundtrips. Occasionally, an insert will trigger a cascade of updates going all the way to the root, requiring all necessary roundtrips at all levels above L. So the total number of roundtrips for ![]() inserts is:

inserts is:

(The last term inside the parentheses on the third line was added to compensate for getting rid of the ceilings in the other terms).

To find the amortized cost for one insert operation, we divide by the number of operations, ![]() , and get:

, and get:

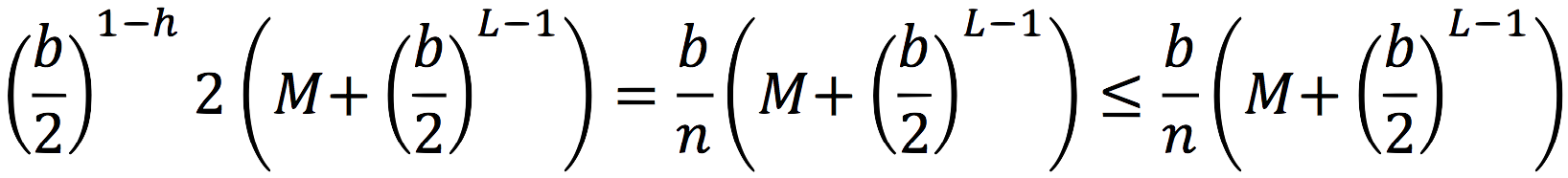

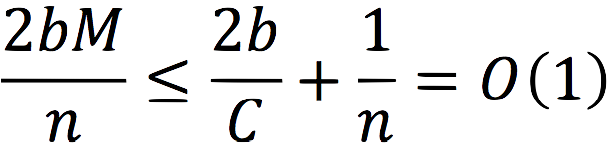

Now, if you look at the definition of L and at the drawing, you'll realize that ![]() , so, finally, we get:

, so, finally, we get:

Let's examine this result. First, if M stays constant, the amortized cost per-operation decreases with n. This actually makes sense. If M is constant and n increases, then the number of nodes stored on each machine increases as well, and more nodes are at levels below L. There's less necessity for inter-machine communication; more of the work is done local to each node. In real life, though, this doesn't happen, as the number of tree nodes that can be stored on each machine is bounded, so when the data-set grows very large, we must increase the number of machines.

If, on the other hand, we increase the number of machines while keeping n constant, the amortized cost rises. This too makes sense. If we distribute the same amount of data to more machines, more of the nodes will be closer to level L, and more inter-machine communication will be needed, since each machine is now responsible for a smaller subset of the data.

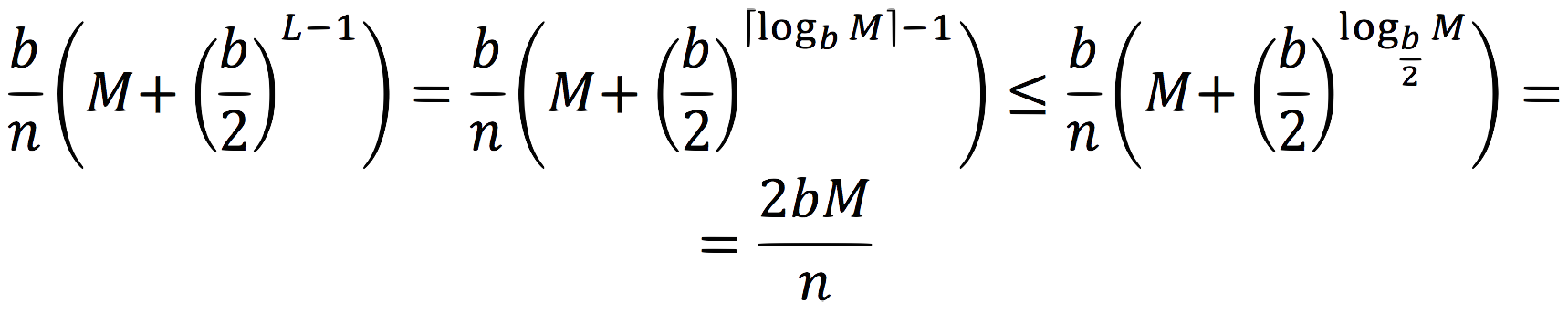

But I think that in real life scenarios, the number of machines is more-or-less linearly related to the size of the data set. This does not mean that we cram as much data to each machine as its RAM can store — we also want each machine to have enough CPU resources to process the information it holds. How much processing is required is application dependent, but for any given application the ratio of processing power per data items stored may either change very gradually or very rarely (say when new users join, and even then this tends to be accompanied by more data) so that it can be treated as constant. If we decide, then, that we want each machine to store and process up to C objects — or tree nodes in our case — M becomes related to n (![]() ), and now our cost becomes:

), and now our cost becomes:

True, this is not the whole story. Once k exceeds h, the height of the tree will grow, requiring some re-balancing, possibly moving some tree nodes from one machine to another. I claim (without rigorous proof), that the number of nodes transferred will be ![]() , and this event will only happen once every

, and this event will only happen once every ![]() inserts, so the two will cancel out.

inserts, so the two will cancel out.

Conclusion

Though we started out by saying that Galaxy sacrifices worst-case performance for common-case performance, when using a data-structure that fits well with Galaxy's distribution model, and assuming the number of machines is related to the size of the data set, not only have we got O(1) (amortized) worst-case performance in terms of network roundtrips, but the actual constant is much less than 1 (because C>>2b), which is what we'd get when using a distributed hash-table. This is perfect scalability, and it is a direct result of the properties of the B+-tree (and other similar tree data structures), and is not true for all data structures.

Also, we have computed the amortized cost of the insert operation, but, as we've seen, within a sequence of such operations, while most inserts entail no network hops at all, a small portion result in quite a few roundtrips, like the rare insert that causes node splits to propagate all the way to the root. The O(1) amortized behavior means that throughput is unaffected by the number of machines (accepting our assumption that machines are added to accommodate processing more data), but the latency of a single, rare, operation might be. Nevertheless, such events are so rare (and Galaxy's heuristics can reduce the write latency in many cases), that even a very latency-aware application — perhaps all but hard real-time systems — are better off using Galaxy's design rather than a DHT tree, provided that their data, and data operations, are well served by a data-structure that fits this design well.

Reader Comments (1)

Why would not post some real benchmark numbers?