64 Network DO’s and DON’Ts for Game Engines. Part IIIa: Server-Side

Wednesday, July 15, 2015 at 8:56AM

Wednesday, July 15, 2015 at 8:56AM

This article originally appeared on ITHare.com. It's one article from an excellent series of articles: Part I. Client Side; Part IIa. Protocols and APIs; Part IIb; Protocols and APIs; Part IIIb. Server-Side (deployment, optimizations, and testing); Part IV. Great TCP-vs-UDP Debate; Part V. UDP; Part VI. TCP.

In Part III of the article, we’ll discuss issues specific to server-side, as well as certain DO’s and DON’Ts related to system testing. Due to the size, part III has been split, and in this part IIIa we’ll concentrate on the issues related to Store-Process-and-Forward architecture.

18. DO consider Event-Driven programming model for Server Side too

As discussed above (see item #1 in Part I), the event-driven programming is a must for the client side; in addition, it also comes handy on the server side. Having multi-threaded logic is still a nightmare for the server-side [NoBugs2010], and keeping logic single-threaded simplifies development a lot. Whether to think that multi-threaded game logic is normal, and single-threaded logic is a big improvement, or to think that single-threaded game logic is normal, and multi-threaded logic is a nightmare – is up to you. What is clear is that if you can keep your game logic single-threaded – you’ll be very happy compared to the multi-threaded alternative.

However, unlike the client-side where performance and scalability rarely pose problems, on the server side where you need to serve hundreds of thousands of players, they become really (or, if your project is successful, “really really”) important. I know two ways of handling performance/scalability for games, while keeping logic single-threaded.

18a. Off-loading

The first way to allow using another core, is off-loading of the heavy processing from the main thread (very similar to that of described in [NoBugs2010], ‘If it walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck…’ section). When applying it to our event-driven model, it would mean our “main thread” creating a request to be offloaded into another thread, starting another thread to process (or post request to existing thread via some kind of queue), and continuing doing other stuff. When another thread is done with computations – it will post a special message into an incoming queue of our “main thread”. For this to work properly, it is important to make sure that at no point non-constant data is shared between threads (i.e. offloaded function should have all it’s input and output parameters passed by value, with no references/pointers to main thread data).

One example of the off-loading implementation might look as follows:

class Offloader { //generic one, provided by the network engine

void process(IncomingMessage&,OutgoingMessage&) = 0;

// IncomingMessage contains input data for calculation

// OutgoingMessage is a reply which will be fed back to "main thread"

// when calculation is done

};

This off-loading approach to multi-threading is very-well-controlled, with synchronization being barely noticeable (and those next-to-impossible-to-find inter-thread races being eliminated), and doesn’t cause much trouble in practice. However, pure offloading scenarios (those which don’t require data sharing between threads), are rare for games, and deviating from pure off-loading can easily bring back all the multithreading nightmares. If you can offload some computation while being sure that underlying data doesn’t change (or data is small, so you can make a snapshot to feed it to offloaded thread) – by all means, do it, but it won’t happen too often.

Another (and usually more applicable to game engines) way is to go beyond single core on the server side, is to use Store-Process-and-Forward architecture, which is described in our next item.

19. DO consider Store-Process-and-Forward architecture

So, you do like single-threaded simple development, but at the same time you really need scalability, and offloading doesn’t cut it for you. What to do?

There exists a reasonably good solution out there, which works good enough in many (though not all) cases.

The basic idea is to separate your system into many loosely-coupled nodes which communicate via sending and receiving messages; as soon as it is done – all each of the nodes can and should do, is merely processing events (with processing for each node staying within a single thread). For example, an interface implemented by a node, may look as simple as:

class Node {//generic one, provided by the network engine

public:

void process_message(const IncomingMessage&) = 0;

};

class MyNode : public Node { //game-specific one

//here goes state of MyNode

public:

void process_message(const IncomingMessage& msg) {

//...

}

};

This model is simple and efficient, and enforces a very-well-defined message-based interface. How to divide the system into nodes – depends on the game, but in practice it can be either different-parts-of-the-same-game-world, or casino tables, or stock exchange floor, or whatever else you can think of (as long as it is loosely coupled and doesn’t require to be absolutely synchronous with the rest of the system). We’ve named this architecture Store-Process-and-Forward (see below why). Each of the nodes in Store-Process-and-Forward system is capable of doing only one single thing – processing incoming messages, and the processing is performed as follows:

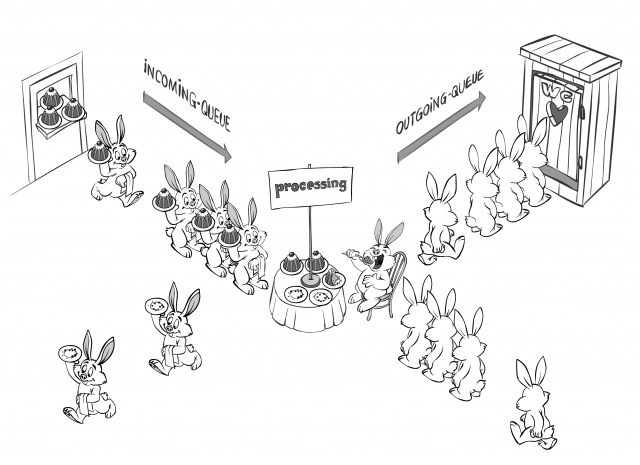

incoming-message -> incoming-queue -> processing (node logic) -> outgoing-queue(s) -> outgoing-message(s)

For those into patterns, each of our nodes can be seen as implementing “Reactor” pattern [Schmidt2000].

Store and forward is a telecommunications technique in which information is sent to an intermediate station where it is kept and sent at a later time to the final destination or to another intermediate station.— Wikipedia —

In a sense, Store-Process-and-Forward architecture is quite similar to store-and-forward processing model as it is used in backbone Internet routers (and which is known to be extremely efficient). With classical store-and-forward model, each node receives an incoming packet, and puts it to an incoming queue; and on the other hand, as long as there is something in incoming queue – the node takes it out, makes a decision where to route it, and pushes the packet to outgoing queue(s). What we’re adding to classical store-and-forward model, is that between taking out a message from incoming queue and sending it out, we’re processing it. Hence, the Store-Process-and-Forward name.

For our purposes, receiving-incoming-message-and-putting-it-to-incoming-queue can be implemented as a non-blocking I/O (in the extreme case the incoming queue could be, for example, an incoming TCP buffer, and I/O can be blocking) or as a separate network thread, and message processing can be implemented as node’s “main thread”. In some rare and specific cases, processing within some of the nodes may be implemented as multi-threaded, but this should be treated as an exception (and such exceptions have been observed to cause those thread-sync problems, so unless really necessary, multi-threading in node processing should be avoided).

19a. Applicability: DO Split the Hare Hair

In general, if you can split your system into reasonably small nodes – you SHOULD use Store-Process-and-Forward architecture (it has numerous advantages which are discussed in the item #19d below). So, the question is: can you split your system or not? Let’s consider it in a bit more detail.

“Node can represent pretty much everything out there - from game-logic-node to database-handling-node, and from payment-processing-node to an SMS-sending-node.

First of all, let’s see what can be represented by a node? We have quite a bit of good news in this regard. Node can represent pretty much everything out there – from game-logic-node to database-handling-node, and from payment-processing-node to an SMS-sending-node. In general, peripheral nodes (such as two latter ones) rarely cause any problems, it is game-logic-nodes and database-handling-nodes (if you need the latter) which may be a bit tricky to separate.

When it comes to splitting your game into game-logic-nodes, think: what is the smallest isolated unit in your game (and/or game engine)? Very often you will find out that you do have isolated units with lots of action within, and very few communications in-between. For a world simulator such a unit can be a cell or a scene (usually the latter), for a casino it can be a table/lobby (note: you don’t need to have all the game nodes to be the same – you can and should make them specific, so it is perfectly fine to have a separate table node and a lobby node, and instantiate them as necessary). You will be surprised how many systems you will be able to split into the small-and-relatively-isolated nodes, if you think about it for 5 minutes.

A word of caution: the best split is usually a “natural” one (like those described above), with direct mapping between existing game entities and nodes. While artificial splits are possible, they tend to cause too many interactions between the nodes, which kills the whole idea. Once again – to be efficient, a node needs to be an entity which contains a lot of logic within, with relatively few communication with the other nodes.

19b. DO Think about Splitting Database-Handling Nodes

In most over-the-Internet games you will need some kind of a database (or some other persistent storage) – at least to keep user database, logins, high scores, etc. etc. On the other hand, in many games you don’t really need to care about splitting database nodes, and one single node will do it all for you. Otherwise, splitting database-handling nodes may become tricky. I know of three approaches for such a split. First is “quick-and-dirty but not exactly scalable”, the second one is “somewhat scalable”, and the third one is “really scalable”.

“I've seen a system which had managed to process 30'000'000 non-trivial database transactions a day on a single DB-handling node, running over a single DB connection.

“Quick-and-dirty” approach is actually delaying DB node split for a while. You have one single DB-handling node (with a single underlying DB); it greatly simplifies both development and deployment (including DBA work). On the negative side, obviously, “quick-and-dirty” approach is not really scalable. However, surprisingly, a “quick-and-dirty” system can work for quite a long time (provided that your DB programmers are good); I’ve seen a system which had managed to process 30’000’000 non-trivial database transactions a day on a single DB node, running over a single DB connection. And if the game is successful enough to exceed these numbers, this model can be changed to the “really scalable” one without rewriting the whole thing (though with significant effort on DB-node side).

Very roughly, “quick-and-dirty” model can be described as follows:

“Somewhat scalable” approach is to have multiple DB-handling nodes over a single underlying DB, while sharing different objects stored in DB, between nodes (if objects are not shared, it is really a version of “really scalable” approach, see below). In general, I don’t really like this “somewhat scalable” thing; one big problem with this approach is object sharing, which creates high risks of running into race conditions (in the worst case leading to game items – or even money – lost in transit), very-difficult-to-track locks (affecting performance in unpredictable ways), and deadlocks (ouch!), making the whole thing tantamount to inter-thread races (which, as discussed above and in [NoBugs2010], are a Really Bad Thing). For some systems, “somewhat scalable” approach might be reasonable, but in general I’d suggest to avoid it, unless you’re 200% sure that (a) it is what you need, and even more importantly, (b) that you’re not going to ask me to fix resulting problems  .

.

Very roughly, “somewhat scalable” model can be described as follows:

It is worth noting that in books and lectures, this “somewhat scalable” approach will by far the most popular and the most recommended one (and often they will also tell you that it is the only way to achieve real scalability). However, in practice (a) it appears not to be linearly scalable (due to intra-database interactions and locks on shared objects), (b) it causes pretty bad problems due to inherent synchronization issues, and (c) among real-world reasonably-large (like “multi-million transactions per day”) systems, at the very least, it is not universal; I’ve seen quite a few architects that admitted using “quick and dirty” or “really scalable” implementations, always feeling uneasy about it because they went against the current teachings. IMNSHO, it is one of those cases when the books are wrong, and practice is right.

“Really scalable” approach usually means that for M gaming nodes you can have N+1 database-handling nodes, (where M is usually much larger than N). Here, each of N database-handling nodes will support a bunch of gaming nodes, and 1 database-handling node will support central user database. Each of database-handling nodes has it’s own database (or it’s own set of tables in the database) where nobody except for this database-handling node is allowed to access. To deal with inter-database-node interactions, you’ll certainly need to provide “guaranteed inter-DB transactions” (implementing them is beyond the scope of this article, but it is doable with or without explicit DB support for distributed transactions). This approach is perfectly free from races, and is scalable beyond the wildest dreams (all the nodes are completely independent, which ensures linear scaling without any risk of unexpected slowdowns, N can be increased easily, and single central user database_handling_node+associated_database pair can be split too quite easily if it becomes necessary). It has been seen to work extremely well even for the largest systems. However, it is a bit cumbersome, so at first you might want to settle for 1+1 database-handling nodes (or even for a single one, making it a “quick-and-dirty” system at first).

Very roughly, “really scalable” model can be described as follows:

As noted above, one could stay within “really scalable” model while keeping data from several database-handling nodes within one database; one database doesn’t make much difference as long as there is no possible locking between the objects stored there. An ideal way to achieve separation is to have each node exclusively “own” a set of it’s own tables; if each node accesses only it’s own tables – using one database for multiple nodes shouldn’t cause any problems (unless you manage to overload DB log, which is usually difficult unless you’re storing multimedia in your database), but it simplifies deployment and work of DBAs quite a lot. On the other hand, while implementing DB-handling node separation at row level (with different DB-handling nodes sharing the same DB tables, but exclusively “owning” rows with a certain key field), is possible, you should keep in mind that even while objects are separated, nodes will still occasionally compete for index locks (because index scans tend to lock not only current row, but also previous/next ones); whether this would cause problems in practice – depends heavily on a lot of factors, including nature of DB interaction, DB load, and specific database (and index type) in use.

A variation of “really scalable” approach (with M~=N) is to say that there are many game nodes which are essentially DB-handling nodes, and which have both game logic and their own DB (for deployment purposes it is better to provide each DB-handling node with their own set of tables within the same DB); you’ll still need to have one central database node with the user DB, and you’ll still need to have guaranteed inter-DB transactions, but overall logic might be significantly simpler than for generic “really scalable” approach. This variation is scalable, simple, and race-free, so feel free to try it if it fits your game  .

.

Very roughly, this variation of “really scalable” model can be described as follows:

“Both these cases allow to have DB processing synchronization-, race- and lock-free

Overall, when you start your development, as a very rough rule of thumb, I’d suggest to consider one of two opportunities:

- “Quick and Dirty” approach, planning to migrate to “Really Scalable” one if the project is vastly successful

- Each-Node-is-DB-Handling-Node (M~=N) variation of “Really Scalable” model.

Both these approaches share one very important property. In both these cases, each DB-handling node has it’s own data, and doesn’t share this data with the others; it allows to have DB processing as deterministic, and synchronization-, race- and lock-free, as node processing under Store-Process-and-Forward. And believe me, races (whether inter-thread, or inter-DB-connection, the latter regardless of transaction isolation levels) are Really Tough To Deal With, especially when the logic changes all the time (and if your game is successful, game logic will change, there is no doubt about it).

In general, the database-handling issue is way too large to fit into one single item of an article; some day, I might write specifically on this subject; for now the most important thing is to realize that databases can be handled easily and efficiently within Store-Process-and-Forward architecture (I’ve seen such systems myself).

19c. DO Think about “I Have no Idea” State

One thing which you need to keep in mind when writing a server-side distributed system, is that when you send a message to another node asking to do something, it can end up in three different states: “success”, “failure”, and “I have no idea whether it has even been delivered”. It is the last state which causes most of the problems: for example, in case when part of server-side nodes fails, and another part stays alive, or when you have some of your inter-node links temporarily failed, what is especially important for inter-datacenter deployments, but does happen within a single datacenter and has been observed even on one single server.

“For inter-datacenter interactions this 'I Have no Idea' state is clearly one of the worst problems"

This “I Have no Idea” state is not specific to our Store-Process-and-Forward architecture, but appears inevitably as soon as server-side becomes distributed (it also appears for communications between client and server, but this is beyond the scope now).

For inter-datacenter interactions this “I Have no Idea” state is clearly one of the worst problems; in particular, I’ve observed it to be (by far) the worst problem when organizing communications with payment processors; from my experience, while all payment processors do address this problem one way or another, only around 1/3rd of them are doing it in a sensible way; others tend to have extremely inconvenient and/or error-prone requirements to recover from it (like “to recover, you need to request all your transactions around the time of failure to see if it went through; oh, and you can’t request more than 2 hours of your transactions at once to avoid overloading our server”).

In practice, these “I have no idea whether it has been delivered” scenarios might or might not be a problem for you, but if you can eliminate this problem in general – you’d better do it.

19c1. DO Consider implementing Explicit Support for Idempotence

Idempotence is the property of certain operations in mathematics and computer science, that can be applied multiple times without changing the result beyond the initial application.— Wikipedia —

One of the approaches to deal with “I have no Idea” state is to have all the messages (or at least all the messages which may cause some kind of trouble) in the system as idempotent ones; idempotence means that the message can be applied many times without any problems (with any number of duplicate messages causing the same result as one single message).

In many cases, it is easy to support idempotence on a case-by-case basis, but the issue is so important that it is better to think about generic support for idempotence. One way to support idempotence for certtain classes of messages, is related to two observations:

- all messages with read-only processing, are naturally idempotent; while reading the data may cause different value being read, under certain conditions (like no other way for the nodes to interact) it becomes indistinguishable on the requestor side from the message being delayed

- all messages for which processing is restricted to a mere update of a certain node state to be equal to received value (in a “x=x_from_message” manner) are naturally idempotent too (provided that certain conditions are met, such as x having only one source of updates).

- it is important to note that messages with even a little bit more complicated processing, are not necessarily idempotent. For example, message with processing “x+=dx_from_message” is not naturally idempotent. The key here is not about simplicity, but about following an exact processing described above

- ordering might be an issue, and implications of mis-ordering need to be taken into account

- this approach works well for non-guaranteed delivery. In particular, Unity 3D’s state synchronization exhibits this type of idempotence.

In addition, if timing is not that important, engine can provide support for all the messages to be idempotent; one such implementation would include:

- have all the nodes to provide their own ID for each and every message

- receiving nodes storing received IDs (for example, one option is to store maximum processed ID if IDs are known to be monotonous)

- receiving nodes checking if the ID has already been received, and handling request differently depending on request being original one or a duplicate one (but providing exactly the same reply in any case).

“If you know that the message is idempotent, and you ended up in a 'I Have no Idea' state, you can always repeat sending your message, while being sure that it will work without side-effects regardless of the message being previously received or not.

No, as we’ve discussed how to implement idempotency, let’s think why idempotency is so important? (ok, it is a bit late to raise this question, but better late, then never). The answer is: idempotency is important because if you know that the message is idempotent, and you ended up in a “I Have no Idea” state, you can always repeat sending your message, while being sure that it will work without side effects regardless of the message being previously received or not. This resending may be handled by application (and there are cases when it is a good idea, especially in real-time scenarios), or can be implemented at game engine level.

19c2. DO Consider implementing Explicit Support for Once-and-Only-Once Guaranteed Delivery

A close cousin of Idempotence is Once-and-Only-Once Guaranteed Delivery. In this case, game engine states that it doesn’t matter if there is a connectivity between nodes or not; in any case, message will be retransmitted as soon as connectivity is restored, and will be processed exactly once. One of the ways to implement Once-and-Only-Once Guaranteed Delivery is to combine idempotence with authomated message retransmit.

Overall, handling of “I have no idea” state in general way is quite complicated; further implementation details (such as DB/persistent-storage handling on both sides if any, generating IDs which cannot possibly clash, etc.) are beyond the scope of the present article, but maybe some day I will elaborate on it; for now – just keep in mind that this “I have no idea if it has been delivered” problem does exist, and if you see how to handle it for your specific case – do it.

19d. Store-Process-and-Forward Advantages

As soon as you have your system split into nodes, and implemented your system as Store-Process-and-Forward one – you’re in real luck. Advantages of Store-Process-and-Forward architecture are numerous (yes, I know I sound like a commercial):

- Your game (and DB, if applicable) developers don’t need to care about threads or races, development is very straightforward, code is not cluttered with synchronization issues and is easy to read

- Store-Process-and-Forward architecture provides very clean separation of concerns and encourages very clean and well-defined interfaces, hiding implementation details in a very strong way

- As soon as you know node state and incoming message, processing is deterministic

- which means that automated testing can be implemented easily

“With proper logging, in most cases bug can be found from one single crash/malfunction.

- It has been observed to simplify debugging and even post-mortem analysis greatly (that is, if you have enough logging of incoming messages). With proper logging, in most cases bug can be found from one single crash/malfunction.

- As game developers have no idea about the way inter-node communication is implemented, game engine framework can allow admins to deploy it as they wish (without any changes to game logic):

- deploy everything on one server (useful for debugging), or

- deploy on multiple servers in single location, or

- deploy on multiple servers in different locations CDN-style, or

- deploy nodes to the cloud

- In addition, different mappings of nodes to processes and threads are possible (again, without any changes to game logic):

- admin may deploy some of the nodes as processes, and

- deploy some of the nodes as threads within common process (saving on process overheads at the cost of less inter-node protection), and

- deploy some of the nodes as multiple-nodes-per-single-thread. This imposes some specific requirements (only those nodes without blocking calls and lengthy processing are eligible), but tends to reduce CPU load significantly if you have 10000+ nodes per server.

19e. DO use Store-Process-and-Forward: Parting Shot

In general, Store-Process-and-Forward architecture certainly goes beyond one simple item, and deserves a separate article (or even a book). It provides quite a few advantages (listed above), and I’ve seen it working with a really great success. A system with up to half a million simultaneous highly active users generating half a billion messages a day, has operated on a hardware-which-was-5x-to-10x-weaker-per-user-than-most-of-competitors, has had response times better than any competitor, all of this with unplanned-downtimes of the order of 1-2 hours per year for 24/7 operation (which can be translated into 99.98% uptime, and that’s not for a single component, but for the system as a whole – a number which auditors considered “too good to be true” until the proof was provided).

Bottom line: you certainly SHOULD use Store-Process-and-Forward – that is, if you can logically split your system into loosely coupled nodes. And if you cannot think of the way how to split your game into nodes – think again.

Related Articles

Reader Comments